Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an infection that attacks the body’s immune system. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the most advanced stage of the disease. There is currently no effective cure for HIV. But with proper medical care, HIV can be controlled.

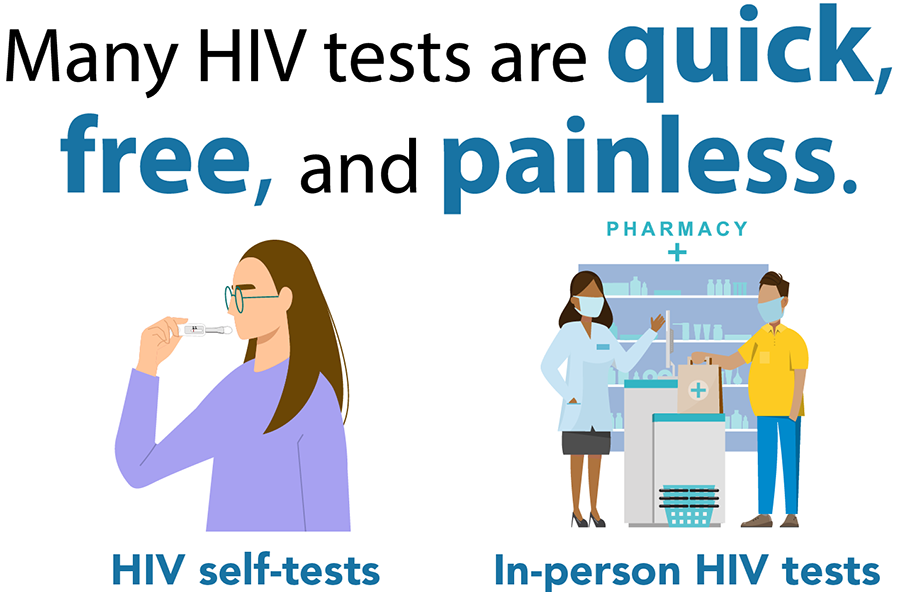

The only way to know if you have HIV is to get tested. Knowing your HIV status helps you make healthy decisions to prevent getting or transmitting HIV.

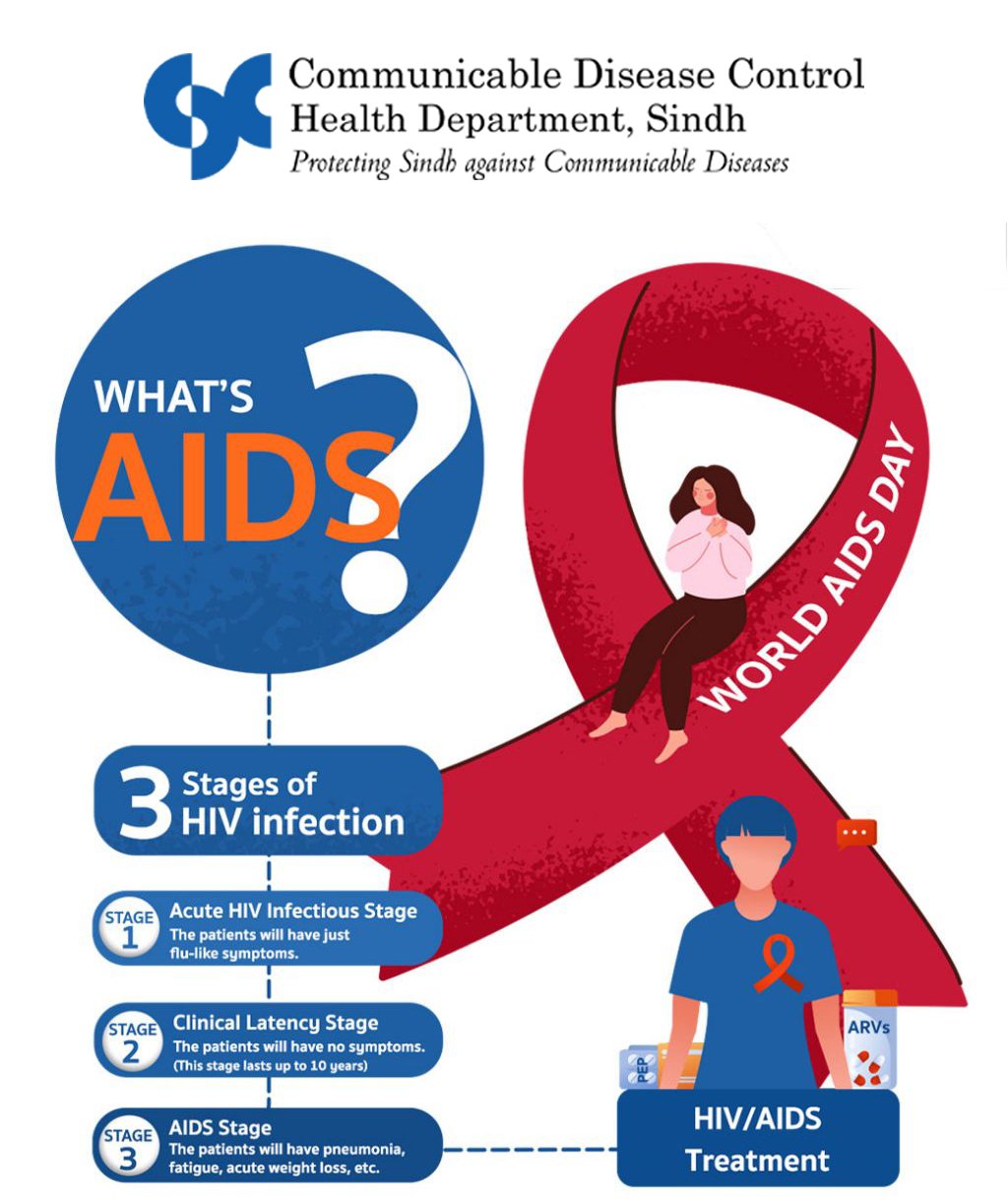

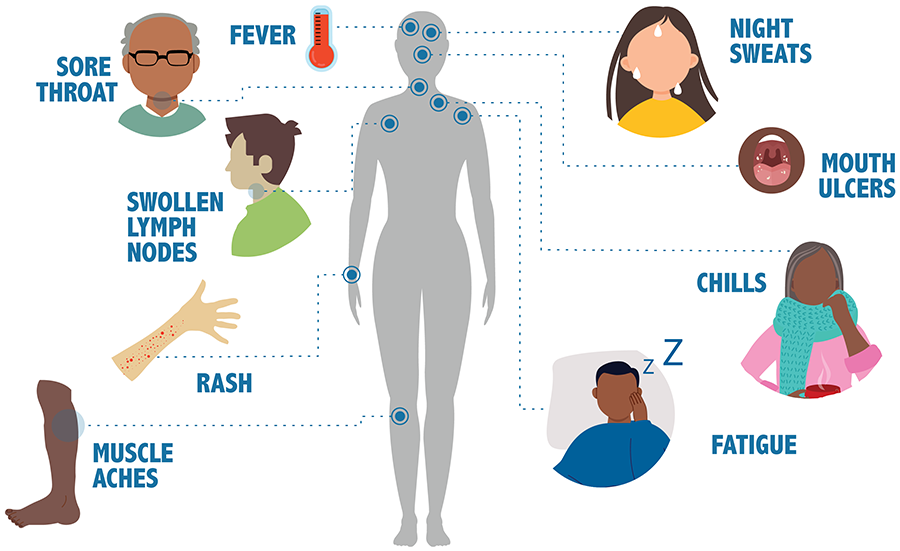

When people with HIV don’t get treatment, they typically progress through three stages. But HIV treatment can slow or prevent progression of the disease. With advances in HIV treatment, progression to Stage 3 (AIDS) is less common today than in the early years of HIV.

Most people get HIV through anal or vaginal sex, or sharing needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment (for example, cookers). But there are powerful tools to help prevent HIV transmission.

You can get HIV if you have vaginal sex with someone who has HIV without using protection (like condoms or medicine to treat or prevent HIV).

HIV can be transmitted from a mother to her baby during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding. However, it is less common because of advances in HIV prevention and treatment.

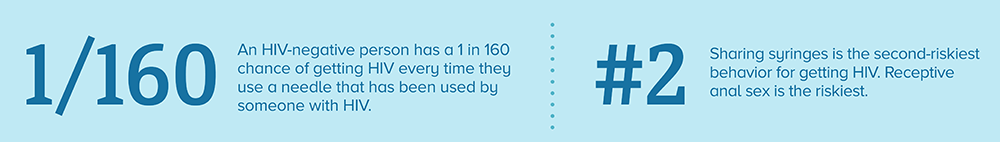

You are at high risk for getting HIV if you share needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment (for example, cookers) with someone who has HIV. Never share needles or other equipment to inject drugs, hormones, steroids, or silicone.

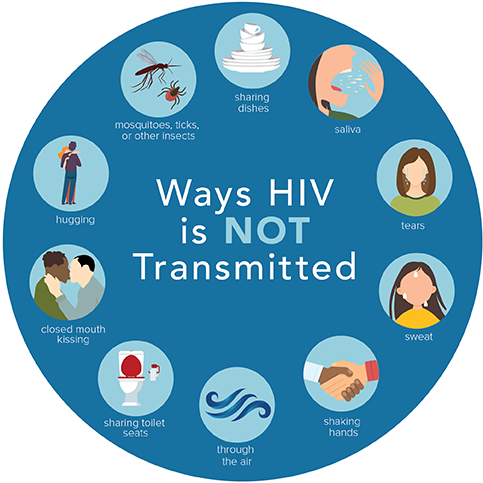

There is little to no risk of getting HIV from the activities below. For transmission to occur, something very unusual would have to happen.

HIV does not survive long outside the human body (such as on surfaces), and it cannot reproduce outside a human host. It is not transmitted

Sharing needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment—for example, cookers—puts people at risk for getting or transmitting HIV and other infections.

The risk for getting or transmitting HIV is very high if an HIV-negative person uses injection equipment that someone with HIV has used. This is because the needles, syringes, or other injection equipment may have blood in them, and blood can carry HIV. HIV can survive in a used syringe for up to 42 days, depending on temperature and other factors.

Substance use disorder can also increase the risk of getting HIV through sex. When people are under the influence of substances, they are more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as having anal or vaginal sex without protection (like a condom or medicine to prevent or treat HIV), having sex with multiple partners, or trading sex for money or drugs.

Sharing needles, syringes, or other injection equipment also puts people at risk for getting viral hepatitis. People who inject drugs should talk to a health care provider about getting a blood test for hepatitis B and C and getting vaccinated for hepatitis A and B.

In addition to being at risk for HIV and viral hepatitis, people who inject drugs can have other serious health problems, like skin infections and heart infections. People can also overdose and get very sick or even die from having too many drugs or too much of one drug in their body or from products that may be mixed with the drugs without their knowledge (for example, fentanyl).

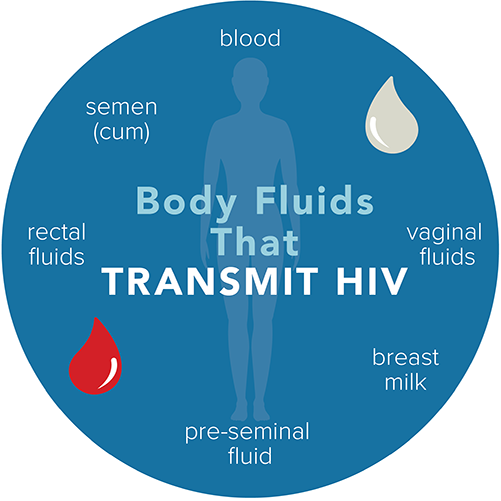

Only certain body fluids from a person who has HIV can transmit HIV. These fluids include

These fluids must come in contact with a mucous membrane or damaged tissue or be directly injected into the bloodstream (from a needle or syringe) for transmission to occur. Mucous membranes are found inside the rectum, vagina, penis, and mouth.

The higher someone’s viral load, the more likely that person is to transmit HIV.

If you have another sexually transmitted disease (STD), you may be more likely to get or transmit HIV.

If you’re sexually active, you and your partners should get tested for STDs, even if you don’t have symptoms. To get tested for HIV or other STDs, find a testing site near you.

When you’re drunk or high, you’re more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors like having sex without protection (such as condoms or medicine to prevent or treat HIV).

If you’re going to a party or another place where you know you’ll be drinking or using drugs, you can bring a condom so that you can reduce your risk of getting or transmitting HIV if you have vaginal or anal sex.

Counseling, medicines, and other methods are available to help you stop or cut down on drinking or using drugs. Talk with a counselor, doctor, or other health care provider about options that might be right for you.

Substance use disorders, which are problematic patterns of using alcohol or another substance, such as crack cocaine, methamphetamine (“meth”), amyl nitrite (“poppers”), prescription opioids, and heroin, are closely associated with HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Injection drug use (IDU) can be a direct route of HIV transmission if people share needles, syringes, or other injection materials that are contaminated with HIV. However, drinking alcohol and ingesting, smoking, or inhaling drugs are also associated with increased risk for HIV. These substances alter judgment, which can lead to risky sexual behaviors (e.g., having sex without a condom, having multiple partners) that can make people more likely to get and transmit HIV.

In people living with HIV, substance use can hasten disease progression, affect adherence to antiretroviral therapy (HIV medicine), and worsen the overall consequences of HIV.

HIV stigma is negative attitudes and beliefs about people with HIV. It is the prejudice that comes with labeling an individual as part of a group that is believed to be socially unacceptable.

Here are a few examples:

While stigma refers to an attitude or belief, discrimination is the behaviors that result from those attitudes or beliefs. HIV discrimination is the act of treating people living with HIV differently than those without HIV.

Here are a few examples:

HIV stigma and discrimination affect the emotional well-being and mental health of people living with HIV. People living with HIV often internalize the stigma they experience and begin to develop a negative self-image. They may fear they will be discriminated against or judged negatively if their HIV status is revealed.

“Internalized stigma” or “self-stigma” happens when a person takes in the negative ideas and stereotypes about people living with HIV and start to apply them to themselves. HIV internalized stigma can lead to feelings of shame, fear of disclosure, isolation, and despair. These feelings can keep people from getting tested and treated for HIV.

HIV stigma is rooted in a fear of HIV. Many of our ideas about HIV come from the HIV images that first appeared in the early 1980s. There are still misconceptions about how HIV is transmitted and what it means to live with HIV today.

The lack of information and awareness combined with outdated beliefs lead people to fear getting HIV. Additionally, many people think of HIV as a disease that only certain groups get. This leads to negative value judgements about people who are living with HIV.

Talking openly about HIV can help normalize the subject. It also provides opportunities to correct misconceptions and help others learn more about HIV. But be mindful of how you talk about HIV and people living with HIV.

HIV is fully preventable. Effective antiretroviral treatment (ART) prevents HIV transmission from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery and breastfeeding. Someone who is on antiretroviral therapy and virally suppressed will not pass HIV to their sexual partners.

Condoms prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, and prophylaxis use antiretroviral medicines to prevent HIV. Harm reduction (needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy) prevents HIV and other blood-borne infections for people who inject drugs.

HIV is treated with antiretroviral therapy consisting of one or more medicines. ART does not cure HIV but reduces its replication in the blood, thereby reducing the viral load to an undetectable level.

ART enables people living with HIV to lead healthy, productive lives. It also works as an effective prevention, reducing the risk of onward transmission by 96%.

ART should be taken every day throughout the person’s life. People can continue with safe and effective ART if they adhere to their treatment. In cases when ART becomes ineffective - HIV drug resistance - due to reasons such as lost contact with health care providers and drug stockouts, people will need to switch to other medicines to protect their health.